By: Danya Perez

Fourth graders passed colorful sheets of paper around on a recent Monday morning at KIPP Un Mundo Elementary School, eager to fold them into paper planes in Luis Arreola’s classroom.

But before they could start turning paper into aircraft, they had to answer two key questions posted on the digital board:

“I will throw my airplane at a _____ degree,” the on-screen assignment read. “I will measure the distance by ____.”

“I know this is super exciting and you want to make your airplanes fast and throw it, but we have to make sure we do it correctly,” Arreola told his students. “An engineer does not rush to make their craft, right, they have to take their time.”

With a show of hands, the students told Arreola which angle they selected – 45 degrees, 90 degrees or 0 degrees – and they all agreed that the distance would be measured using a meter stick.

Then the fun part began. One by one, the students walked to the front of the class and to the sound of “Three, two, one!” the colorful paper planes shot into the air — some way farther than others.

Monte Bach/San Antonio Express-News

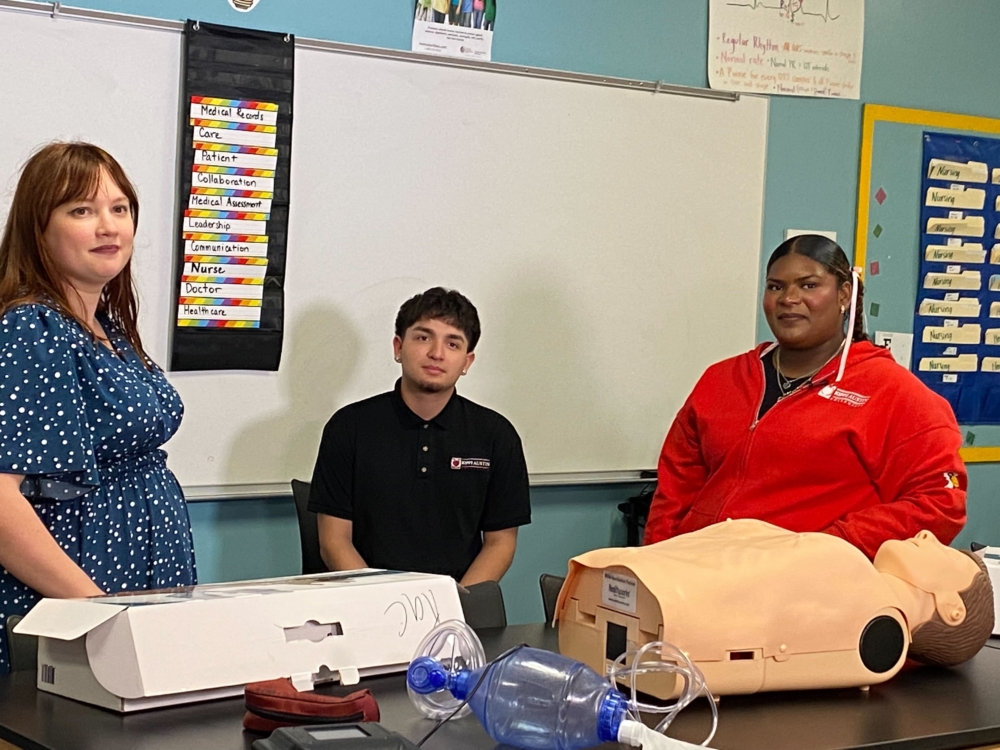

Un Mundo is one of many charter schools starting their 2022-23 school year with a new sense of progress after a couple of years of coronavirus-related interruptions.

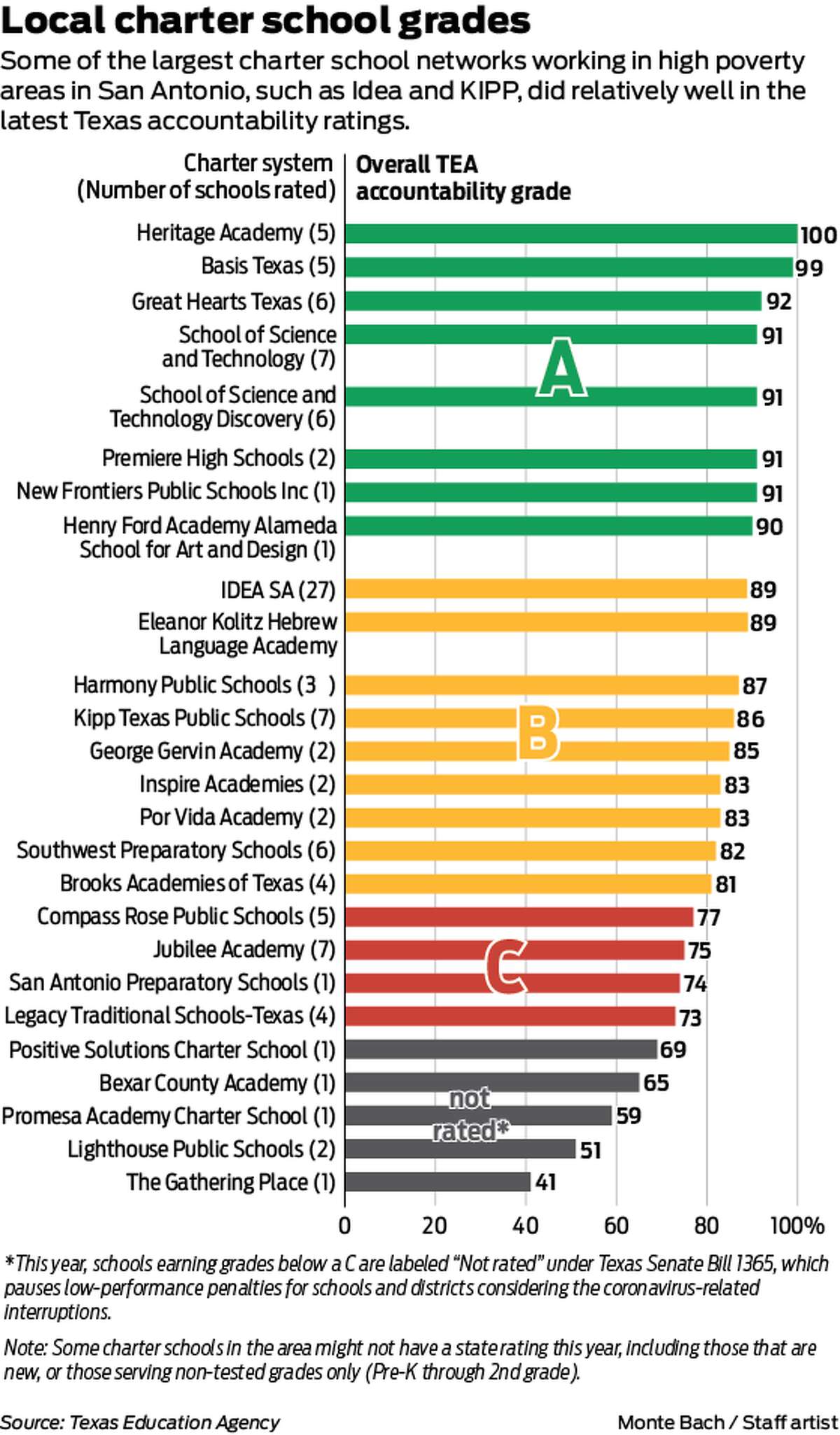

As with traditional public school districts, area charter networks improved in overall student performance in the Texas Education Agency’s newly released statewide accountability ratings, and for the same reasons — the scoring system rewards growth, and many schools whose test scores fell into the basement in the 2020-21 academic year went to extraordinary lengths to pull them back up.

In 2019 – the last year TEA issued the A-F ratings before pausing due to the pandemic – Un Mundo, along with KIPP Esperanza Elementary, had F grades, with scores of 54 and 46, respectively.

This year Un Mundo earned a B, with an 84 score. The statewide network, KIPP Texas Public Schools, earned a B and an 86 overall, with six of its seven San Antonio schools earning Bs and the other a C. The network had a B in 2019, too.

But charter schools, mostly those located in high-poverty areas, also were among the public schools that didn’t recover from the pandemic’s disruption and damage and slipped in the state accountability ratings.

In San Antonio, the charter school network with the most underperforming schools was Jubilee Academy. Six of its seven area schools were “Not rated” and one earned a C score, Jubilee Westwood.

This year, schools earning grades below a C are labeled “Not rated” under the state’s Senate Bill 1365, which put a pause on penalties for low performance.

The TEA rates schools based on three domains: Student Achievement, School Progress and Closing the Gaps. The rating system still rests heavily on student performance on the State of Texas Assessment of Academic Readiness, or STAAR test, but since 2018 it has also considered factors such as year-over-year growth regardless of where a student started, graduation rates and career and college readiness.

All of Jubiliee’s schools in San Antonio earned scores below a C in student achievement. Only two earned a C in academic growth and school progress.

Jubilee officials did not answer continuous requests for comment in the weeks following the release of the statewide performance data. The network is based here but has expanded to the Rio Grande Valley, Kingsville, and Austin. Over the past school year, it reported an enrollment of nearly 3,000 San Antonio students and more than 5,700 across the state.

Other “Not Rated” charters in the area included Positive Solutions, Bexar County Academy, Promesa Academy, Light House Public Schools and The Gathering Place. Most of these networks have only one school rated by TEA this year. Light House has two.

Larger charter networks fared better, including the largest, IDEA, which had 27 schools rated in San Antonio, of which 17 earned an A and 10 earned a B. The charter network earned an overall B grade with an 89 score.

Harmony Public Schools also got a B, with an 87 score. One of its three San Antonio campuses, Harmony School of Innovation, was “Not Rated,” with a 65. The other two earned Bs.

KIPP – which originated in Houston but is now headquartered in California – has 59 campuses in Texas.

“We focused on social and emotional learning,” said Daphne Carter, the network’s academic officer. “We actually spent the first couple of weeks of school really getting our students back and learning how they were doing, sort of responding to any trauma that they were dealing with, and then we jumped into academics.”

The result, she said, was “tremendous growth in our San Antonio schools.”

All students at KIPP Un Mundo, from pre-K through 4th grade, have a new class chart this semester called the “Mastery Tracker,” in which they get to see their level of understanding of each subject, measured with daily “objectives” or questions that summarize the lessons.

“Kids know their data, too, on a daily basis,” Paula Salas, assistant principal of instruction, said. “So, they are super invested in making sure they are gaining the objectives that they need.”

Charter networks that earned an overall A grade this year include the School of Science and Technology, Great Hearts Texas, Basis Texas, Heritage Academy and Premiere High School.

What to consider?

Educators across the region differ on how much weight to give the state’s A-F grading system for schools but agree the scores should be one of many things families consider when choosing where to enroll their children.

Inga Cotton, who has two children in charter schools and founded San Antonio Charter Moms, an information resource to involve parents in school choice, considers the state metrics helpful and includes the scores in the nonprofit’s guide to charter schools in the region.

But schools are more than a score, and parents need to consider curriculum, campus culture and overall alignment with their needs and values, she said.

“There’s definitely valid reasons why a family may choose to keep their child in a school that has a C, D, or F rating,” Cotton said. “It might be that the school has a really strong sense of community. It might be that there’s a lot of enrichment, or extracurriculars, or the school model … but the key thing is, don’t let your child fall behind academically.”

Even in a high-rated school, families might not always find the academic support that fits their child, she said, so it’s important to keep an eye on their annual STAAR report cards and year-over-year growth.

Cotton also suggests parents know the ratings of all the schools in their neighborhood, to assess what options are nearby.

Kat and Theodoro Gomez have a fourth-grader, Karina, at Brooks Academies of Texas’ Lone Star campus – which earned a B and a score of 87 this year, up from a C and 78 rating in 2019.

She transferred there amid the pandemic from The Gathering Place, which has only one testing grade, 3rd grade, and was deemed “Not Rated” this year. Previously, they chose not to place Karina in their neighborhood school, San Antonio ISD’s Maverick Elementary.

Campus culture and her child’s adjustment were the main reasons for the move, not scores, because while she loves data, the family now knows better than to place all its trust in a number, Kat Gomez said.

When they decided against Maverick, “I put so much weight on that rating when I didn’t know much about schools,” Gomez said. “I just wish people understood that that is just one aspect and that doesn’t mean that’s a bad school. But people gravitate towards those ratings, even though there’s so many other things that go into what makes a school great.”

This is part of what educators across the state have warned for years, even after the TEA system was revamped to include more than just STAAR scores and more nuance than the old pass-fail rating.

Other measures

Brian Woods, superintendent of Northside ISD, the regions’ largest, has been outspoken about his dislike of a statewide system that doesn’t acknowledge the different types of success or failure that students might experience.

“If we are going to really measure schools, what we need to start with is for parents, or for community members, (to) tell us what you think students should be getting out of school. And tell me what you think the benefits of public education are,” Woods said.

The answers will likely vary from city to city, and even from neighborhood to neighborhood, Woods said, but what most people remember from their time in public schools are meaningful relationships, programs that truly fit their interests or those that helped them find a career path or skill.

In San Antonio and across the country, performance in state accountability systems has historically reflected the poverty level of the community in which a school is located.

Some of the low-performing charter schools in this year’s report card show that relationship. Most of the Jubilee campuses are in areas where the San Antonio, Northside and East Central ISDs also have some low-performing schools.

Jubilee Lake View University Prep, for example, was deemed “Not Rated” this year, earning a score of 58. About 91 percent of its students are economically disadvantaged, and about 20 percent are English learners.

It’s a Pre-K through 12th grade school. The nearest SAISD schools are Rhodes Middle — also deemed “Not Rated” by TEA, with a 65 score — and Carvajal Elementary, which had a C and a 79 score. Both schools’ student populations are more than 95 percent economically disadvantaged with at least 20 percent English learners.

For parents wanting, or needing, to keep their students in the same neighborhoods as the failing Jubilee schools, most of the nearby public schools earned Cs or were similarly “Not Rated.” A handful got Bs.

For such families, the scores measuring student growth could be the main deciding factor, to see “if the school is helping kids progress,” along with the availability of classes or programs that interest their kids, Cotton said.

Woods said the scores are a look back at what the schools did over the past year, not what they are doing now. When considering student growth, many non-testable areas should be considered, such as involvement in arts, extracurricular activities and career development, he said.

“What I find to be a shame is that years and years ago we generally agreed in this country that there are lots and lots of ways to be smart, to be talented, and we don’t have a system that measures very many of these ways,” Woods said.

As seen on the San Antonio Express-News here.